The Romantasy Era: The Growth Of Female-Centric Sci-Fi & Fantasy Versus The Manosphere

Image Source: Marie Claire

I’m an avid fan of science fiction and fantasy, what the literary world might call speculative fiction. I grew up reading Star Wars novels and, in high school, I was introduced to The Lord of the Rings, and my fascination only grew from there. For a time, in college, I made a short jaunt into the nonfiction world, being a history major, and obsessively read history and politics. I still maintained my speculative obsession, however. Throughout that time, it’s usually been portrayed as a male-dominated field, from characters to authors. Sometimes you’d get an exception, but it felt like they stood out among the flood of male authors.

That’s obviously changed. More and more female authors are writing SF/F, and that’s a great thing. It means more books to read, and more stories to become engrossed in. One of my favorite series is by Becky Chambers. Her Wayfinders series is incredible and moving. Others have come to redefine the genre and stake a place for women in the genre, like V.E. Schwab, Delilah Dawson, and more.

RELATED:

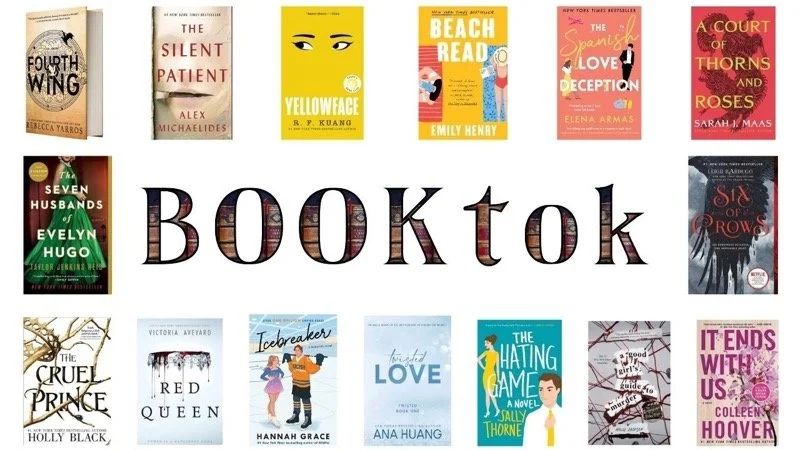

Lately, in my full embrace of my book addiction thanks to BookTok (I dream of walls in my house covered in books), I feel like I’ve noticed a trend, a diminishing of space in bookstores to what has historically been portrayed as typical science fiction and fantasy. These would be your Ursula K. LeGuins, your Kevin Hearnes, George R.R. Martins, Tolkiens, etc. Depending on which store you go to (I’m currently sitting in a Barnes & Noble writing this), it seems like the SF/F section has shrunk, while the YA section has exploded, and now, thanks to BookTok, the Romantasy section has outgrown the usual SF/F area.

Now, before you crucify me, understand that none of this is a problem. It’s more people reading, more people experiencing the genre I love in their own way, and that just means more attention to the genre as a whole. I love that.

Image Source: Cinema Blend

But I won’t lie that I feel like it’s harder to find something to read. I have relatively little interest in most YA, and the same for what’s become known as Romantasy (and I jokingly call Sex Dragon). I tried to read Fourth Wing and I couldn’t make it more than 100 pages in. It just doesn’t work for me, and that’s alright. I’m not being forced to read it, so I don’t. I don’t disparage people from reading it, either. It is what it is about the market, and I’ll discuss that later.

Then I saw a post that became the impetus for this column: John A. Douglas.

That’s right folks, we’re wading into the toxic waters of the “modern male crisis” that has been overblown by the far-right to use as a means to justify their attacks on women and minorities. I think the trend I mentioned above has been noticed by others, those with a chip on their shoulder at the perceived loss of their privilege, and with the reach of the internet and this “modern male crisis”, they’ve found something they think they can exploit to further confirm their biases.

Now, hear me out, 'cause I know I’m not doing myself any favors by saying the following: I have to admit: I kind of see it.

I also want to preface this by admitting I am on the spectrum and have ADHD. So. I have some peculiarity quirks and I’m incredibly picky about what I read.

Anyway.

When I say I kind of see it, I mean I can follow the dots. I don’t agree with it, but I can see how they’re connecting the dots.

Image Source: Bookstr

I’ve talked about this endlessly with my best friend. We regularly go to Barnes & Noble every other Saturday because it’s when we can get together regularly and sip coffee and smell books (there’s no better smell than new books). She reads the Romantasy stuff. As I said, I do not. On the one hand, I find romance in SF/F perhaps out of place. What I mean is, the characters are on this adventure, right? They’re being harrowed by enemy forces, fighting for life and death, trying to solve mysteries and all this stuff. Who has the time to focus on a budding relationship or romance? See, I’m odd. I will refer you back to my disclaimer above.

As a writer, I get it. This stuff happens along the way, it’s part of the character’s journey, it fleshes out the characters and their personality, etc. What’s funnier? I’m a hopeless romantic. I want that love story. I like happy endings. I get that we all have needs. But I struggle with it in fantasy books. Again, I refer you to my statement above.

In our talks and reflection, I’ve reasoned through this a lot. I joke with her that people are only reading the Yarros, Maas, and numerous other books for the sex. I don’t know if that’s underscoring a commentary on the state of the dating world, but, again, whatever. If that’s your kink, you do you. I won’t lie though, it triggers something in my head as a writer that makes it come off as cheap. Gotcha moments and shock value. Taking this back to TikTok, when these books come up on the feed, so many videos that reference these books are about the anatomy of the male characters. I think it highlights Americans’ contradictory view of sex (they act all prudish about it in their media, yet the porn industry is one of the biggest industries in the world). I mean, I do the same thing with Game of Thrones. The first book was published more than a decade before the show aired, and then the series blew up with the popularity of the show and I think the popularity of the show was the shock value (the violence, the sex) and the writing and story came second.

Despite all of this, I don’t care. I think it’s a reflection of our society as a whole, and the shifts we’re undergoing. Women are finally gaining more of a share of the market, no longer relegated to the sidelines (despite current political trade winds). Conversely, men, and young men in particular, are acting like they’re on the margins now. There’s data behind this. More young men turned right-wing in the recent election than ever before, falling prey to the political whimsies of podcasters like Joe Rogan, Andrew Tate, and other right-wing grifters taking advantage of the perceived “masculinity crisis.” Young men increasingly report feeling lost and alone, without a guide to navigate the turbulence of their teenage years and confronted with an ever-increasing supply of messaging that men are under attack, the world is on fire, and women should rule. At increasing levels, they turn to these right-wing “manly” men who tell them what they want to hear. The so-called “manosphere.”

Image Source: Gamespot

What does this have to do with books? If you’ve been exposed to this “sphere,” you’d hear talk about making money, masculine values, and whatnot. Those don’t really include reading books about dragons, elves, or magic. If they’re reading, they’re about reading books on personal wealth, manliness, history, etc. That’s where men are largely featured. History has been male-dominated for, well, ever. Men still make up the majority of seats on corporate boards. The talking heads and podcasters who are “defending” men are men (and oddly some women). One only has to look at the video game industry to get what I’m saying. The vitriol that unleashes when a woman protagonist is revealed for a game gets instantly labeled by the right wing as “woke” and anti-man.

Really though the publishing world, especially the traditional publishing world, is a business. It all comes down to money. Capitalism requires constant growth, and stagnation is bad, and if that’s what is going to make them the most money in the SF/F realm, then that’s what they’re going to publish. It’s working. Maas and Yarros and their counterparts have entire sections for their works. It’s a boon for the industry, and if that means fewer male-centric SF/F novels are getting a share of the shelf space, that’s the market (isn’t that the almighty god of the right?). We have to also remember that the publishing industry is limited. There are only so many traditional publishers, and they’ve been gobbled up like everything else, and only so many agents and editors, so the big publishers are going to direct their resources and personnel to push this genre. It’s making them money which keeps them open.

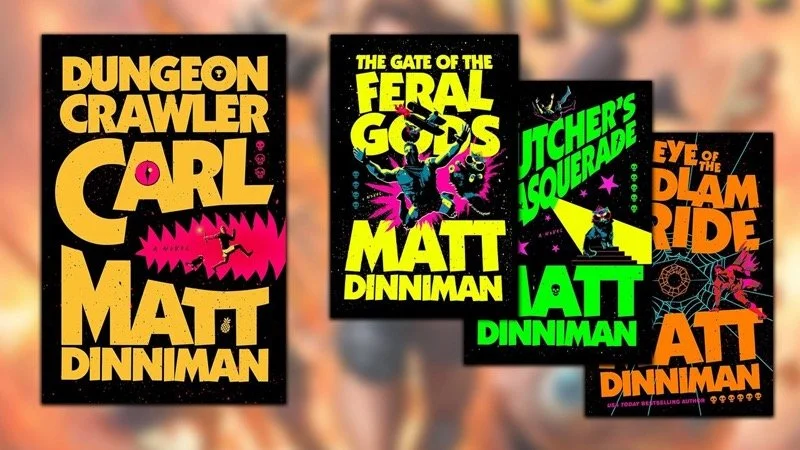

It’s important to have perspective. Men still have their day in the sun. Some of the biggest names in SF/F remain on top. George R.R. Martin, despite his lack of finishing the Song of Ice and Fire, still commands people’s attention. Game of Thrones was a smashing hit, appealing to men and women alike, and women are notoriously treated horribly in the books and show. Andy Weir became a massively successful author, and he published independently. The Martian did so well on Amazon that he got a deal from the big publishers and a movie. Check out Project: Hail Mary, it’s a fantastic book, and it’s being adapted. Recently, another self-published series that turned wildly popular is Dungeon Crawler Carl. All of these are male-dominated and wildly popular.

But here’s the secret folks. If you don’t like it…don’t read it. Live and let live. If you don’t see what you like, branch out, find something new, touch some grass, or write it yourself. Like the guy in the tweet did.

Just don’t be a misogynist like him.

Till next time.

READ NEXT:

Media Literacy 101: Lesson Three - Why

Image Source: LinkedIn

Hello Class.

I know it’s been a while since our last session on Media Literacy, but I’m here today to finish it up. We’ve talked about the “what” and the “who” of things we read and see, which are vital parts of the media literacy skill set. They’re doubly important to this final lesson in the series because when you look at the previous two, this one will make more sense. And then the coolest part of the process, the “aha” moment when everything sinks in, is when you practice the skills learned today, pieces start to fall together, and you start to see the bigger picture.

The skill we’re working on today is “why".

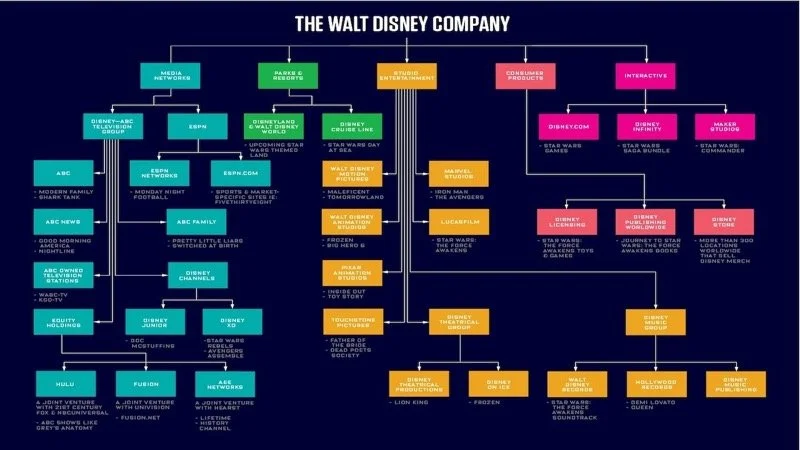

First, let’s start with a discussion on understanding something about the media. In the United States, most of the media we consume is owned by a handful of massive corporations. Our government is feckless when it comes to reining in companies from getting too big, so much so that corporations have significantly more influence over our legislative process than the people do. As a result, only a few companies control the onslaught of information that flows toward us.

RELATED:

Let’s remember, as well, that what we consume is information in all different formats. We also have to remember that these corporations, while they seem like behemoth machines, are still operated and directed by individuals. Individuals have agendas, and when they’re in those positions of power, there isn’t really anyone to check their agenda, except maybe shareholders. All together, though, those individuals and the collective shareholders want nothing more than to make more money. Profit over everything, baby!

A prime example is the situation between Israel, Palestine, and Lebanon. Ironically, through the reporting of other media outlets, we’ve learned that board rooms and the executive suites of major news organizations from CNN to the BBC are bringing the hammer down on the language used to present the conflict to us, the consumers. Words like “genocide” and the like are redirected if brought up by speakers or completely avoided by the anchors. The headlines of newspapers use the passive voice when talking about Palestinian or Lebanese victims to avoid any sort of implication of Israeli responsibility, but the complete opposite is true when the victims are Israeli.

Image Source: Wired

These decisions impact millions, and perhaps billions. Most people consume without question and go about their lives. And it’s not even restricted to just the national and global broadcasts. The disappearance of the local newspaper over the past couple of decades is a prime example, followed by the carving up of local news broadcasts by giant corporations. There’s a great video (linked below) that shows the chilling effect of this when Sinclair started buying up local news broadcasts.

Where, then, should we get our reporting from? The easy answer would be independent news agencies, but even then, be cautious. Independent news outlets rely on subscriptions and donations to stay afloat. Those donations don’t always come from great and honorable sources, and, much like shareholders, if they don’t like what is being published, they could pull their funding. It’s not common, but it’s an ever-present fear. Even with funding, though, it’s not always enough. Many journalists, either out of a job because of cuts or disillusioned with the corporate model, have turned to freelance work. They have flocked to sites like Substack, where you can directly subscribe to their pages and support their work. They lack the resources that come from an established institution, but if they’re reputable reporters (see my “who” article for a refresher), you’re getting the dirt direct from the reporter, sans executive suite filtering.

Now, with all that said, let’s get to it.

What does “why” mean in media literacy?

The TL:DR of it is basically motivation. Human beings are biased animals. We have preferences, we have agendas, and we want people to listen to us. The “why” revolves around the motivation for a piece of media being made, whether it be a video essay or an investigative piece from a journalist. You’ll do this a lot more when you’re just starting to put media literacy into practice because it takes a bit of time to think through things and evaluate motivations. But like the other two, the more you do it, the more it will just come naturally. You’ll find yourself scrolling your feeds and only paying attention to the journalists you know are legit and reputable, and you might even subscribe to their reporting or their YouTube page.

Pay attention to the platforms people use to broadcast their message. The Daily Wire is notoriously far right on the political spectrum, and none of those people are journalists. Anyone, and I repeat, anyone can put a video on YouTube. Just because someone has a massive following on streaming sites does not imply they are an authority on things. We live in a world obsessed with content, and much of it is particularly stupid and only there for brief entertainment. A lot of kids today, when asked what they want to be when they grow up, say they want to be a YouTuber or an influencer. Why is that? Because it gets at the crux of why “why” is one of the most important things to ask when evaluating a source online.

To be fair, not everyone does things for money. But also, to be fair, because of the system we live in, we have to have money to survive. Until we achieve our Star Trek utopia, we’re stuck with material possession-based realities. Kids want to be influencers and YouTubers because of monetization. If your content is popular enough, it gets monetized, and you start to earn money for the stuff you put out there. As I said above, we’re content obsessed, and much of it is stupid entertainment. Watch any Mr. Beast video. I’ll say this again: anyone can put something on YouTube.

Image Source: PolisPandit

Sadly, money is one of the strongest motivators, and a lot of the money backs up the negative, vitriolic, and false information that dominates our attention on the internet. It comes down to our basic psychology. It’s easier to be mean, and we like watching drama. It gets clicks, and clicks equal dollars. It’s why you don’t see fluff pieces on the local news all the time. It’s always crime. Keep the populace scared, and they’ll constantly tune in to make sure they know what’s going on. Ya know, for safety.

Much like politics, if you follow the money, you’ll understand why people do what they do and say what they say on the internet. Tim Pool’s latest controversy is a prime example. There has been a noticeable change in his rhetoric about the Ukraine war within the last few years, and then we learned this year that Tim Pool is a person of interest in a case by the FBI where media influencers were receiving large payments by Russia to promote Russia-positive news. Always. Follow. The. Money.

This is not all without hope. Like I said, there are good sources out there, and while they do feel pressure from above, many, like I said, are using the same tool the liars are using to fight back. Check out people like Taylor Lorenz and Ken Klippenstein. They both previously worked for larger institutions and then went out on their own, taking their following with them to continue to do great reporting but answerable only to themselves, taking all the fire, and keeping us informed. They’re real heroes.

READ NEXT:

Source(s): YouTube

Media Literacy 101: Lesson Two - What

Image Source: LinkedIn

Welcome back, class!

Class is now in session.

Today, we’re continuing the exploration of the issue of media literacy, and we’re going to examine the issue of what is being said in media.

Last time we examined the who element of media literacy and being skeptical about the person telling us things online or on TV. I debated doing one long lesson about who and what because they are closely linked. When you read or watch something online, what is being said is just as important as who is saying it, because if the who is not trustworthy, it’s doubtful what they are saying is factual or legitimate. The inverse is the same as well, and that’s where we are going to focus our attention today.

Let’s start our discussion of what with not what they are saying, but what they are not saying. It’s just as important to criticize the substance of the article or the video as it is to note what they leave out. We can’t include everything in a particular piece of writing or a video. No one has that kind of time and articles or videos would be too long. However, when people are writing articles or making videos, they actively and unconsciously choose what to include and what not to include. This is why the next lesson is the most important, where we’ll discuss the why, but we are saving that for another week.

RELATED:

I’ll give you an example from recent news. The horrible school shooting in Georgia this past week quickly found its way into culture wars again, when alt-right, fascist grifters attempted to spin the narrative that the shooter was a member of the LGBTQIA+ community. Why? Because an article by CNN included a phrase where the shooter had expressed frustration over the acceptance of transgender people. CNN has since changed that phrase to the shooter expressing frustration at the acceptance of transgender people by society.

The Newsroom often depicted an anchor who wanted to pursue news where they held people to what they said and questioned them on it.

Image Source: Michael Cavacini

Note that phrasing. This is at the heart of what I’m saying. Words have meaning, and the way they are arranged into a sentence has meaning as well. Writing requires conscious choices, but it’s also a product of unconscious priming. Our actions are the result of both conscious reactions to external stimuli, but beneath the surface, our lived experience shapes our mentality and can guide those conscious choices. It’s why in class, I will often stop what I’m saying and think of the right word to use because one word can convey an entirely different meaning than another.

Keeping this in mind, when you read or watch something, do the same things I talked about in the previous lesson. Stop. Think. In this frame, since we’re talking about the what, using the same strategy, take some time and go see what is being said by other outlets. Is it time-consuming? Yeah, but practicing this often can lead to faster analysis. When you do this often enough, you’ll begin to see how other outlets cover the material, and it will begin to highlight to you what is and what is not said at each particular outlet. A great example of this is culture war issues. There are people on social media who practice this literacy daily and will list out what the headlines are at different news outlets to show you how some issues are ignored entirely by politically motivated outlets.

Another part of the approach is to ask yourself what you just watched made you think. What questions did it raise in your head? This is a good thing because it leads to more information, and with media literacy, more information is never a bad thing. Without it, it can lead down rabbit holes, but the chances are that people with actual media literacy won’t go down those rabbit holes. Those holes work on a whole subset of psychology that social media algorithms work on. They play on confirmation bias and the need to belong.

Take a look at the Star Wars grifters out there. What are they always complaining about? Break down the themes of their complaints and it always centers around women, people of color, and sexuality in the franchise. We’ve already talked about who they are and questioned their credibility there. When you do that, and then critique what they say, their legitimacy breaks down even further. They know what they’re doing. They know it’s easier for people to just accept anger and fear instead of looking into what they’re saying, and that there is a deep, innate human connection to feel like you belong.

Despite the online grifters, the Star Wars community is its strongest element.

Image Source: DapsMagic

Aside from murder, one of the worst things you can do to a human being is to exile them. Exclude them from the group. These grifters know this, either overtly or subconsciously, and they offer a “community” to those who don’t question what is being said and have been raised in an environment that fosters the kind of hate they seek to confirm. It’s why they say such outlandish things that don’t hold up to any pressure. The minute you feel that connection, hear that thing that you feel, but from someone else, and then see affirmations in the comments, they have a hold on you. But it’s not a foregone conclusion. There is hope.

Much of the lessons learned here are internal. You have to have conversations with yourself. Ask yourself: am I agreeing with it because it confirms what I already feel? Again, take your time. Stop. Think. Ask more questions. How do they know what they know? What do other people say? How are they saying it? What does it make you question? One of the most important questions to ask as you dig into these things is: does it make sense? It’s a tricky one to ask because it’s easy to fall victim to their grift. The grifters are successful because there’s an element of sense to what they say, but it’s only surface-level culture war bullshit that really doesn’t have any weight on our lives.

This brings us to the hardest to tackle and the nail in the coffin of every grifter’s scheme: the why.

That’ll be the subject of next week’s lesson.

Class dismissed.

READ NEXT:

Media Literacy 101: Lesson One – Who

Image Source: Linkedin

Welcome back, all. Class is now in session.

There’s a lot of stupid people out there.

I know that’s harsh but it’s true. For many of them, it’s not their fault, really. They don’t know any better. Either they didn’t pay attention in school, they didn’t further their education, or they just haven’t seen the light yet. There’s still hope for them.

For the willfully stupid, well, you can’t save everyone.

Because of the interconnectedness of the world these days, it’s more important than ever that people know how to be literate in media, especially when billionaires who think themselves to be tech geniuses buy social media platforms and let any kind of bullshit be posted on there (seriously, if you see what appears on the scroll of X these days, it’s incredibly harmful).

So, that’s where I step in. I am here to help train you in the art of media literacy.

RELATED:

Before we start, understand that this comes second nature to me, I don’t even have to think about it anymore, and I still have slip-ups. You will mess up. You will make mistakes. You will be duped by things on social media. That’s ok. Keep a growth mindset and eventually, you’ll get this to a level of a reflex. It took time and training to get to this level.

To begin, you need to cultivate a curious mindset. Like that Ted Lasso scene in the bar, be curious, not judgmental. Ask questions and question everything. When I say question everything, I'm not talking about going off the walls and wearing a tinfoil hat. I’ll expand upon this later, but when something is said to you, or you read something, and it makes you wonder, follow that rabbit. How do you do all this? Simply stop. After you read something, watch something, hear something, stop. Take a minute and think about what you just saw or read.

Ted teaches Rupert a lesson in humility by telling him the story of where "be curious, not judgmental" comes from. Barbecue Sauce.

Image Source: X

What do I mean by think? Again, this comes second nature to me, but I know how I got to this point. I read. I’ve been educated. The points I cover later will help educate yourself, but one of the best things you can do is read. Read everything. News. Research. Documents. Novels. Non-fiction. Everything. Not just posts on X or Facebook (especially not on Facebook). Read actual published work. There’s a reason why I made that distinction, and I’ll get to that.

Before we go on, it’s also important to make this point. Check yourself. When you read or watch something, check your own bias. Do you find you’re agreeing outright with what’s said? Probably not a good sign. We call that confirmation bias in psychology. Humans actively seek out information that confirms what they already believe in their heads. Just because something is natural to humans doesn’t mean it’s a good thing. We haven’t made it this far by blindly following everything we naturally do. We got here by questioning things and resisting the urge to just go with those natural tendencies.

When we’ve stopped to think after reading or watching something, one of the most important questions we should ask is: who? Another thing we tend to do when we’re told something or read about something is to just accept it when we know who the person is. It’s easy to do with visual formats, or on sites like Facebook or X, where you can see who the person is before reading it. When that person is a celebrity or a perceived authority like one of the talking heads on cable news, it predisposes us to accept what they say.

This propensity was demonstrated by psychologist Stanley Milgram nearly 60 years ago. Milgram was the son and relative of Holocaust survivors. He was a fundamental psychologist of note in the field for his work on obedience and the influence of authority, and he wanted to know why everyday people followed Hitler’s orders. His most famous experiment set up everyday people in a situation where they had to read questions to a perceived “student” who would then be shocked by increasingly higher levels of voltage. All of which were heard by the subject. If the subject (the person reading the questions) expressed a desire to stop the experiment, a confederate in a lab coat reminded them that they must continue.

The Milgram Experiment. The confederate is in the lab coat, and the subject of the study is seated in the chair. The "shocking" device is in front of him on the table.

Image Source: Medium

The discovery was that a majority of the subjects went all the way to a lethal dose of electricity. The twist? No one received any shocks. It was a ruse. We can discuss the ethics of the design another time. It demonstrated the effect of perceived authority on our willingness to ignore our moral compass. The study has been replicated numerous times, all with similarly disturbing results. Popularity and renown are not and should not be a prerequisite for blind obedience.

Instead, the importance behind “who” has more to do with reputation for veracity. The best example to look at for this is a journalist. Journalists, the vast majority of them, went to school for their trade. Why should that make us trust them? Standards. Say what you will about standardized tests and whatnot, standards are important for several reasons. Their existence comes from being agreed upon by experts. Think about the field of medicine. While there are cases in which you may need to step outside the box and find a new solution, the vast majority of situations in medicine are handled because there is a standard way of approaching the solution.

It’s the same with information dissemination. Journalists are trained in following leads and verifying facts through corroboration. They don’t just take one person’s word on something, they take that statement, find another person who can verify, and even then they may try to corroborate the corroboration. Journalists are trained researchers. Journalism schools seek accreditation. While they don’t need to be accredited by the Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications (there’s also no “license” for being a journalist), it’s a sort of badge of honor. It’s a stamp that suggests to people that the school has high standards and expectations of their journalists-in-training. It’s all about professionalism. Journalism is a field that stands on reputation and trust. Without it, it collapses, as does the reporting of the truth. Hell, journalists go to prison for refusing to reveal the name of their source when it hurts the government’s feelings. That’s how seriously they take it.

So, considering all that, asking who is perhaps the most important thing to ask when you take in information. Does the guy you’re watching on YouTube have that credibility? Did he corroborate the facts? What about the guy writing the article you read? This is what good readers and thinkers do when they read something or watch things. Sure, this seems like a lot to do just to read or watch things, but the more you do it, and the more people you follow that you’ve already checked out, the quicker it comes to you and the faster you can move on to other things to ask about what you took in.

See you all next time, when we’ll discuss the “what.”

READ NEXT: