What Is Going On In The Gaming Industry? An Analysis

Images Source: IGN

Ask a game developer how they’re doing lately and they're likely to come back with a response that includes words along the lines of stressed, worried, angry, depressed, and so on. Why? If you don’t follow the video game industry, you may be unaware that for the better part of a year now, there has been a slew of massive layoffs within the industry. One of the worst was Microsoft’s layoff of nearly 2,000 employees in the Xbox division.

That’s just one example. In these early months of 2024, there have already been over 8,000 layoffs, and that’s on top of the nearly 10,000 in 2023. There were layoffs at Electronic Arts, Embracer Group, Unity, Sony, Epic Games, Riot Games, and the list goes on.

Why is this happening? What’s going on in the industry? Never mind the human toll of these actions, the answer’s going to take some nuance.

First and foremost, we need to understand a few things.

RELATED:

For one, the seismic shift seems to be happening within the AAA games area of the market. This includes the major, big studios. Secondly, the gaming industry has been in a state of transition for a few years, and like anything that goes through transitions, change is often messy, reactionary, and happens some time after the trigger. Game development is long, with the average length of development, from conceptualization to delivery being nearly five years and getting longer. It’s often quiet for most of the game’s development, and each studio is different in what they decide to let out about the games they are developing.

Image Source: Kotaku

With that in mind, sometimes things happen within the industry that no one expected, like a pandemic, or an approach to a game that people didn’t see coming becoming massively popular. There is a time within the development window that adjustments can be made, but it’s a gamble. If a developer or publisher sees dollar signs from a new model that is a big hit on a recent release, and they think it’ll work for their work in progress, they may shift direction mid-development. But will it pay off for them, or will it be “old news” by the time of release? Or, as was done during the pandemic, studio execs made massive financial decisions that seemed to work at the time, but as the pandemic has faded into the background, their decisions are purportedly causing financial strain now that has been cited as part of the reason for the massive layoffs.

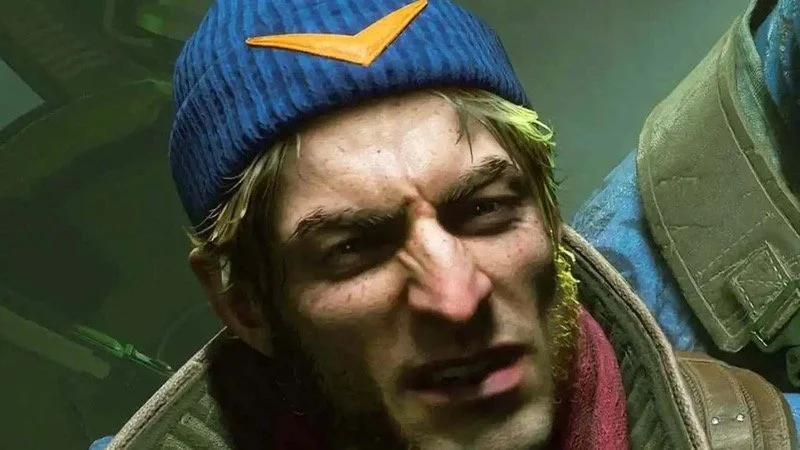

Take the live-service boom we’re currently experiencing. Kotaku reported that back in February nearly 500 studios were working on live-service games. The publishers have fully swung toward the live-service model, but by the time the games come out, there’s no guarantee that players will want to keep playing those types of games. They’re rather hit or miss, an example being Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League being a total flop, but Helldivers 2 being an absolute smash hit. Staking a future on this type of game, when your game may not release for another handful of years, and the fickle nature of gamers, is incredibly risky. The consequences are also delayed, and when they aren’t good, the ones making the decisions aren’t punished, the workers are, as we’ve seen with the contraction currently plaguing the industry.

Image Source: PC Gamer

Phil Spencer, head of Microsoft’s gaming division, sat down with Polygon to try and explain what is going on within the industry, and kind of said the quiet part out loud. Despite how you may feel about capitalism, his talk with Polygon reveals where the gaming industry is struggling and where we’re likely to see a shift in the coming years.

According to Spencer, the rising cost of games, which is getting higher and higher, puts pressure on publishers to make decisions on less risky ventures. We can see this in Hollywood, with studios green-lighting remake after remake rather than making new movies. From a business perspective, and this is a business, that’s a red flag and deters creativity when your IP’s success depends on the fickle and ravenous nature of the consumer base.

Furthermore, the age-old restrictive nature of the game industry is coming up against the ballooning costs of games, and by that, I am of course referring to exclusivity. Making such massively expensive games and then only releasing them to a corner of the market that owns the console that it’s exclusive on is really just bad business sense. This is an industry that exploded on the competition of the consoles, but that was a time when games didn’t cost nearly this much to make. Spencer seems to have read the writing on the wall and has initiated moves at Microsoft to broaden the reach of their games, most recently by announcing that four first-party games would be available now on PlayStation 5 and Nintendo Switch.

Lastly, he talks about how the pool of consumers isn’t necessarily growing. He used the word “upgrading” to describe how the supply of gamers is adjusting, by getting a new console. It’s symptomatic of how capitalism works, and the pursuit of more and more profits. Eventually, you will reach a point where you aren’t bringing in more new users, so the competition just begins to eat itself. It’s not realistic to expect you can reach everyone.

Image Source: Mercury News

The model of perpetual profit forces companies to look for ever more new means of making money toward the pursuit of higher profits every year. When there’s a contraction in the slightest sense, the reaction is job cuts, no matter the cause of the contraction. Combining that with Spencer’s insight, AAA companies are pulling back and cutting fat to maintain those profit margins. It’s a reactionary response to decisions made years ago and an anticipation of where they think the market is going, but their predictive success is not exactly trustworthy. A report recently came out showing that nearly 60 percent of playtime on games in 2023 went to games that are six years old or older.

Things will settle, though, and there are some good things to come out of this disruption. Smaller studios will likely pop up with those veterans who were laid off, and the success of the smaller teams lately is a promising sign that an indie revolution could be coming.

READ NEXT: