How ‘Turning Red’ Continues The Trend of Focusing on Growing Pains

Image Source: Disney

Films from Disney/Pixar have started to stray from clear-cut villains and turned their attention to the interpersonal relationships among their characters. This includes their relationships with friends and family, how they handle the world around them, and sometimes having to change the dynamic they grew up in. Disney/Pixar’s Turning Red recently garnered attention for “encouraging teens to disrespect their parents” and being “too mature” for a younger audience while missing the plot of the protagonist trying to prove themselves and seek approval from older generations.

Like its predecessor, Encanto, Turning Red focuses on the life of a young teenage girl. The difference lies in Mei having to handle the high expectations placed upon her by her mother. Mei’s story centers on herself and the difference in how she interacts with her friends as opposed to her family. Though familial disconnect is nothing new in Disney, the way Turning Red handles the subject is more relatable.

RELATED:

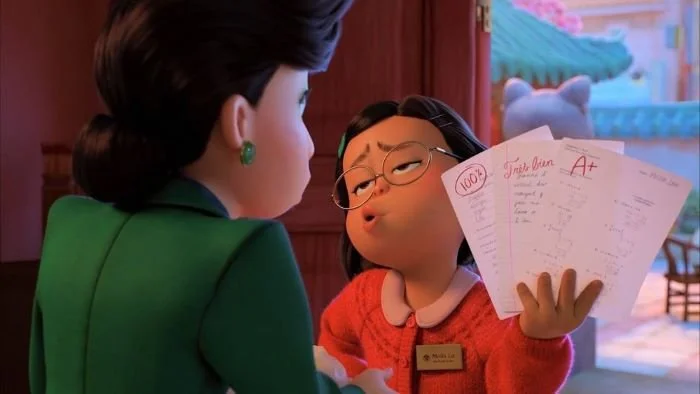

Right away, Turning Red sets itself apart from other Disney/Pixar movies by having its main character interact with its audience. Meilin Lee introduces herself as a 13-year-old “adult” who makes her own decisions. This is in contrast with her earlier declaration of “honoring [her] parents” by “doing every…little thing” asked of her. Even Mei herself admits in a voiceover that while she “makes her own moves,” it’s normal that “some of those moves are [her mother’s].” While it is clear the two love each other, it is also evident that Mei cannot express herself fully. Her mother Ming voices disapproval of the boy band Mei loves (something Ming is unaware of) and one of her friends, Miriam.

If you break down the plot in most Disney movies, there is bound to be a conflict between the central character and their parent(s). Mei works to be the perfect daughter: getting straight A’s in school, doing her temple duties, assisting her parents in making dinner, and participating in a plethora of extracurriculars. Mei’s need to be the perfect daughter correlates with her earlier statement about honoring her parents. They “gave her life,” and in return, she strives to be the daughter they want her to be. It is a seemingly harmless notion with a potentially deadly mindset.

Image Source: Disney

Perfectionism is a double-edged sword. There is nothing wrong with working hard and achieving the best possibility. However, failure is a pill no one wants to swallow. This feeling is amplified when the thought of letting down one’s parents is put into play. Mei is not prepared for the possibility of disappointing her parents, let alone her mother. The worst things Mei ever did were being a few minutes late to work one time and coming in second place in a spelling bee when she was younger. Then, Mei comes face-to-face with her hormones when she suddenly develops a crush on a convenience store employee.

Since her mother views Mei as her perfect little girl, she assumes the worst and reprimands the employee for “taking advantage” of her “innocent child.” The scene sets up the sad reality that Mei has to hide aspects of herself from Ming as she faces changes that she has yet to fully understand. This manifests in her transformation into a large red panda. Her panda appears when she feels any intense emotion like anger, frustration, and embarrassment.

Image Source: Disney

When Ming discovers Mei has started to go through this change, she reveals that not only is she aware of this transformation but that there is a way to “cure” it. The “cure” is a ritual where the spirit of the red panda is removed and locked into a pendant (or another form of jewelry). Even though the spirit started as a gift, Ming is quick to stress how dangerous and unpredictable the red panda is and how important taking part in the ritual is. However, Ming’s solution to simply get rid of the spirit like the rest of her family did little to help their family dynamic.

While Ming tries to do better with Mei than her mother did with her, Ming still passes along the high expectations that her mother put on her. This is evident when her family’s unexpected visit causes Ming to revert to a quiet and obedient child who fears her mother’s disapproval once again. Despite the distance, Ming still could not escape the pressure of being the ideal daughter for her mother. This had caused a rift in a once close relationship between the two when Ming “tried to be a good daughter” and prioritize her family first above adolescent experiences and milestones.

When Mei reveals her involvement in using her panda for money, she shatters the image of being Ming’s innocent “little Mei-Mei.” As she talks about how she wants to keep her panda spirit (something her friend Miriam suggested under the pretext of “not losing all of [herself]”), Mei also declares that she’s a thirteen-year-old girl who likes “boys, loud music, and gyrating.” Mei only wants her mother’s permission to go to the concert.

After a heartfelt talk with her father, Jin, Mei remembers the good parts of her panda spirit while acknowledging the bad. This breaks the cycle of suppressing the messy parts of herself as her family did. She realizes the danger of repression and ignoring aspects of one’s personality just to please others. Mei experiences this notably in the film when she comes face to face with a younger version of her mother in the spirit world.

Image Source: Disney

Seeing Ming so vulnerable when she was about the same age as herself causes Mei to realize how similar she and her mother are. Mei empathizes with young Ming, acknowledges her feelings, and assures her that she is indeed good enough. Mei guides Ming through the forest as Ming grows back into her adult self and banishes her panda spirit again. In the end, Ming realizes how much Mei put others before herself, just as she did, and that she regrets having passed that down to Mei. She tells Mei, “Don’t hold back for anyone. The farther you go, the prouder I’ll be.”

Mei’s growth brought Ming and Mei closer. The two are seen having more open conversations, including their father in the family business, and are better connected to their respective pandas. Acknowledging the more destructive aspects of themselves might not have been ideal, but it is part of growing up. Had Mei and Ming continued their relationship as it was at the beginning of the film, it is safe to say it would parallel Ming and her mother’s, and the cycle would continue.

Turning Red invites the audience to consider taking the leap as Mei did, embracing the messier aspects of life, and acknowledging its existence. As Mei says, “We all got an inner beast. We all got a messy, loud, weird part of ourselves hidden away. And a lot of us never let it out. But I did….” What are the next steps ? It’s up to us.

Image Source: Disney

READ NEXT:

Source(s): YouTube